A nyone who has had a lease reviewed by us in the last few years will know that there are multiple producible formations underneath the property they have leased. This is excellent for royalty owners, as the more formations can be produced the more gas can be produced. There’s just one problem with that. It means that the lease that you sign today could possibly be in existence decades, or even centuries from now.

nyone who has had a lease reviewed by us in the last few years will know that there are multiple producible formations underneath the property they have leased. This is excellent for royalty owners, as the more formations can be produced the more gas can be produced. There’s just one problem with that. It means that the lease that you sign today could possibly be in existence decades, or even centuries from now.

Ignoring the happy fact that the lease will be in effect because the producer will be paying you royalties, let’s look at what the implications of a decades-old lease are. The easiest way is to look into history.

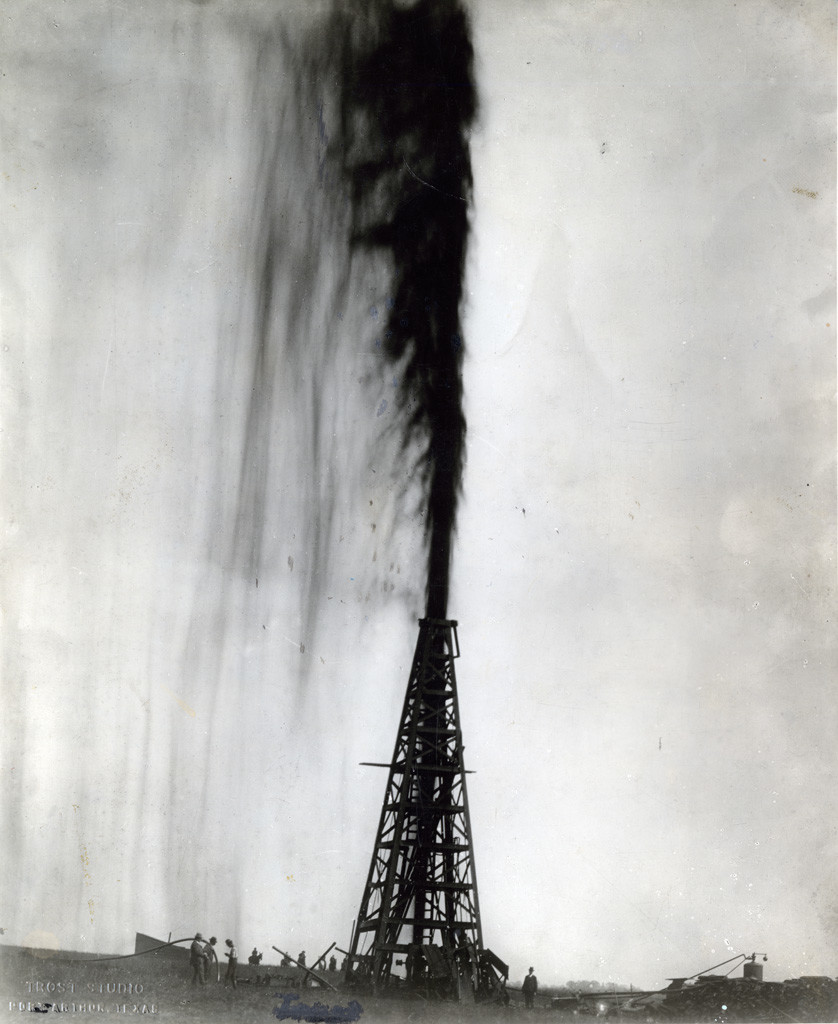

In 1892 a farmer (no names will be used here so as to preserve my clients’ confidentiality) signed a lease on property here in West Virginia. The producer was diligent, and drilled a well on the property within a few months. The well produced gas, which was something of a disappointment because everyone was looking for oil at the time. They didn’t shut the well in though because the producer allowed the farmer to run a pipe to the house and use the gas for heating and cooking.

Over the years gas became a valuable commodity, and the developer put a line of his own to the well and started selling the gas. Of course, the producer paid royalties to the farmer, and all was well. Eventually though, the well produced less and less gas.

Let’s fast forward to today, and that well that was drilled in the late 1800s is still producing in 2015. The production has dropped off to a few hundred MCFs per year. The royalties paid are only a few dollars each year, but it’s just enough production to keep the lease alive.

Now let’s back up to 2007, when the Marcellus boom was just taking off. The current producer of the well was just a small time mom and pop operation. They didn’t have enough money to drill a Marcellus shale horizontal well on their own. They were approached by a big producer who wanted to buy the rights to produce gas from the Marcellus, and the mom and pop jumped at the chance to make some good money from the old lease. They assigned the rights to the Marcellus shale over to the big company for thousands of dollars an acre.

Along with the rights to develop the Marcellus shale came the rights to use the surface in any way that was “fairly necessary”. The big company approached the current owner of the farm. The big company said they wanted to put in a well pad, an access road, and a pipeline. The well pad was going to take up about 10 acres of mostly flat land (flat land is hard to come by in most parts of West Virginia), the access road would be 1/2 mile over property the farmer hunted on, and the pipeline was going to be across other property the farmer owned. All told, the development was going to take up about 15 acres of the farm.

The farmer said no. The big company said, “we have the right to do this because we have this lease that was signed back in 1892, and that lease gives us the right to use the surface in any way that is fairly necessary for the development of oil and gas.” The farmer said, “I don’t see that in there.” The company said, “no, but the courts have said that any lease gives the company that right.” The farmer consulted with a lawyer, who told him the big company was right, but that there were some legal arguments to make and he could take the big company to court, but it would cost $10,000.

Back in 1892 when the first farmer signed the lease, he didn’t expect a well pad, road, and pipeline to take up 15 acres of his good farmland. A well pad took up maybe an acre, and the access road was usually nothing more than a jeep trail. The pipeline was usually just a couple inches in diameter, and was sometimes laid on the surface over rough ground. He had no way of foreseeing the size and extent of modern well sites. If he could have seen into the future, he probably would have made some changes to the lease before he signed it.

That’s just one example of how a lease surviving for decades could be detrimental to those who inherit it, or those who inherit the property affected by it.

It’s impossible to foresee every possible way that a lease could affect people in the future. You can’t protect your heirs from everything. It is possible, however, to do the best that you can with the information that is out there now.

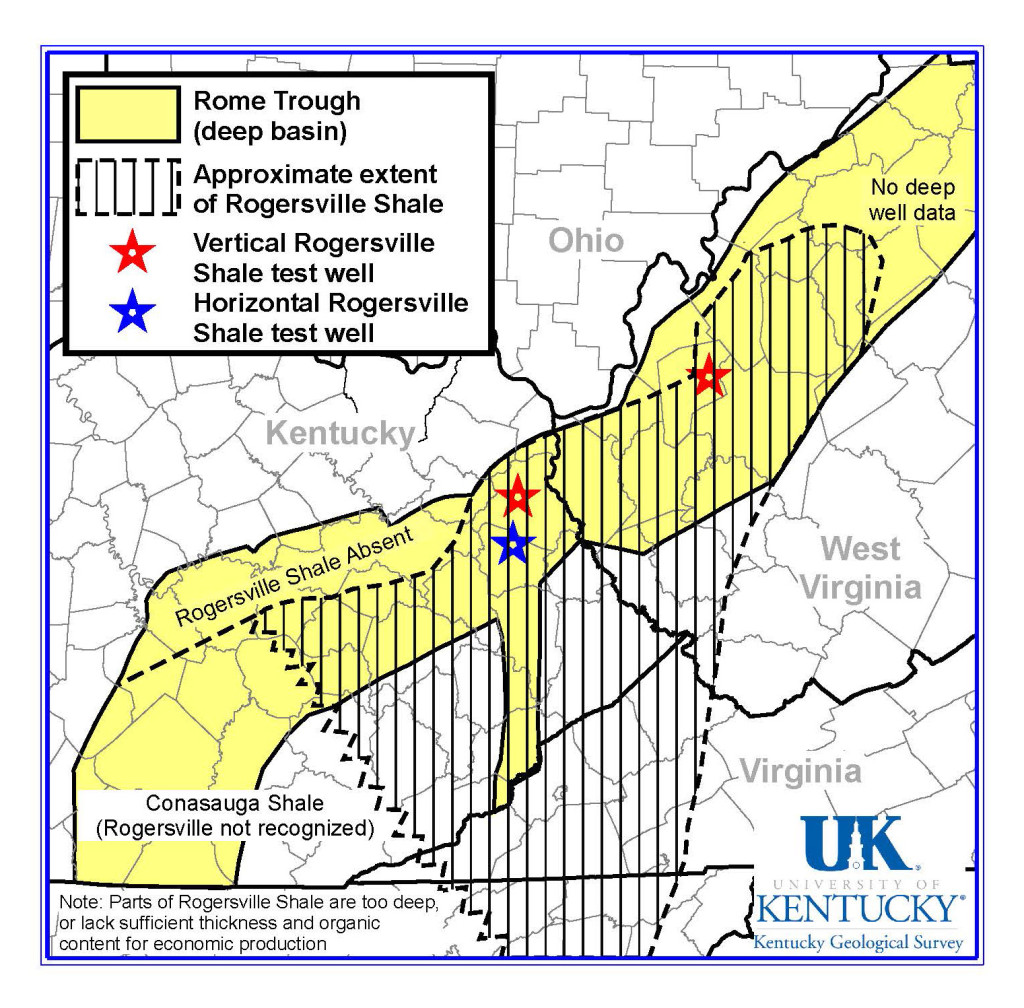

Multiple formations mean that oil and gas companies could produce one formation until it is exhausted, then a second formation until it is exhausted, and then a third and maybe even a fourth. It’s impossible to tell for sure how many producible formations are down there. It’s impossible to tell how long the lease will stay alive.

The reason we’re pointing this out right now is that Rex Energy has completed wells to the Marcellus and the Upper Devonian on the same property in Pennsylvania. The Marcellus produced reasonably well, but the Upper Devonian actually produced a little better. It’s been questionable up until now whether the Upper Devonian would be a good formation to explore. That question is now laid to rest, at least to some extent.

For our West Virginia mineral owners, keep an eye out for leases that include the Upper Devonian. We can look forward to increased exploration in the usual counties; Tyler, Wetzel, Marshall, Doddridge, Harrison, Ritchie. There may be a renewed interest in Barbour, Upshur, Taylor, and some of the other counties in the Marcellus dry gas area. We hope so, as we have clients who are waiting on leases in those counties.

For everyone that’s thinking about signing a lease — do try to think about the future as much as you can. If you need some help, give us a call.